Itineraries

There are lots of things to do in Valbona, although in the past we never really organized any of these for visitors (silly us!). Over the winter we’re working on developing itineraries for cooking, handicrafts, traditional farming, horse-riding and wolf-watching (seriously!), as well as botanical walks, but . . . er, none of that’s ready yet. In the meantime, the jewel-in-the-crown of Valbona has to be the unparalleled ability to wander to your heart’s content through the wildest landscape in Europe.

There are lots of things to do in Valbona, although in the past we never really organized any of these for visitors (silly us!). Over the winter we’re working on developing itineraries for cooking, handicrafts, traditional farming, horse-riding and wolf-watching (seriously!), as well as botanical walks, but . . . er, none of that’s ready yet. In the meantime, the jewel-in-the-crown of Valbona has to be the unparalleled ability to wander to your heart’s content through the wildest landscape in Europe.

Hiking, Walking & Trekking

- Chatty notes about Hiking in Valbona

- Difficulty Levels

- Frequently Asked Questions

- List of Trail Names

- Trail Descriptions

Some Notes on Walking by Yourself in Valbona:

We want to be very clear about is this: Hiking in these mountains is not safe. They gained the name “Bjeshket e Nemuna” (Accursed Mountains) precisely because invaders lacking the locals’ knowledge of navigable paths tended to simply disappear. If you set off and try to find your own way you are very likely to get stuck somewhere nasty. Over hundreds of years, the local people have built up knowledge of the specific paths which will allow you to get somewhere (and more importantly, back again!), and as of 2011 some of these paths will be cleared and marked for the adventurous hiker. However, as Alfred often says when asked about a path: “It is not difficult, but it is dangerous.” There is by definition no way to make these mountains safe, as their steep and crumbly limestone geology makes landslides, avalanches and flash flood cataracts an everyday (or more precisely an every-rainy-day) occurance. The only thing that can make the walker safe is that person’s own care and caution. To paraphrase Arthur Ransome “If not duffers, won’t die.” With that said, we invite you to explore the most wild and unspoiled landscape in Europe. You are quite likely to spot signs of the numerous wild boar, wolves and brown bears, although they’ll (probably) leave you alone. You will almost certainly hear rocks being kicked down from above (hopefully not direcly above, but we’re not making any promises) by the wild moutain goats, and if you’re lucky and sharp-sighted, you may see groups of a dozen or more roaming the mountain tops. For botanists, the over 300 species of endemic plants make these mountains a paradise, especially in early summer. And those of the “Because It’s There” mentality can enjoy weeks’ worth of challenging slopes with the reward of stupendously stunning views. We hope you will love it as much as we do.

We want to be very clear about is this: Hiking in these mountains is not safe. They gained the name “Bjeshket e Nemuna” (Accursed Mountains) precisely because invaders lacking the locals’ knowledge of navigable paths tended to simply disappear. If you set off and try to find your own way you are very likely to get stuck somewhere nasty. Over hundreds of years, the local people have built up knowledge of the specific paths which will allow you to get somewhere (and more importantly, back again!), and as of 2011 some of these paths will be cleared and marked for the adventurous hiker. However, as Alfred often says when asked about a path: “It is not difficult, but it is dangerous.” There is by definition no way to make these mountains safe, as their steep and crumbly limestone geology makes landslides, avalanches and flash flood cataracts an everyday (or more precisely an every-rainy-day) occurance. The only thing that can make the walker safe is that person’s own care and caution. To paraphrase Arthur Ransome “If not duffers, won’t die.” With that said, we invite you to explore the most wild and unspoiled landscape in Europe. You are quite likely to spot signs of the numerous wild boar, wolves and brown bears, although they’ll (probably) leave you alone. You will almost certainly hear rocks being kicked down from above (hopefully not direcly above, but we’re not making any promises) by the wild moutain goats, and if you’re lucky and sharp-sighted, you may see groups of a dozen or more roaming the mountain tops. For botanists, the over 300 species of endemic plants make these mountains a paradise, especially in early summer. And those of the “Because It’s There” mentality can enjoy weeks’ worth of challenging slopes with the reward of stupendously stunning views. We hope you will love it as much as we do.

Difficulty Levels

Exhaustive (or at any rate exhausting) research into the various systems used around the world for rating hiking trails has led us to the following conclusions: 1. There are too many of them (almost everyone seems to have their own, from the Swiss, to the Yosemite, to the Brazilian to New Zealand, just to mention a few), 2. They are highly subjective (ususually by their own admission), 3. There’s no good reason for adopting one over another, and 4. Whether they use numbers, letters or words (our favorite here has to be the “French Adjectival System” whose hardest rating according to Wikipedia is”Abominablement difficile (abominable)”), they most usefully center around just how badly you’ll hurt yourself if you fall down the worst part of the trail, with basically three levels: Easy: If you fall you’ll just hurt yourself a little; Medium: Plan on breaking something serious; Hard: You’re dead.

With that said, we’ve decided to give you as much information as we can, and rely on your good sense to decide what you’re capable of, or at any rate what you want to try. Thus descriptions of trails will tell you: 1). The total kms from the start to the end (sorry for pointing out the obvious, but this means you have to double this if you plan on returning the way you came). 2). How long we think it will take the average walker, one-way. A note here: We recommend that you use caution – or at any rate extreme skepticism – when asking local people to estimate walking time, as the fact is that your average Malesori 10 year-old can probably walk three times as fast as you – sorry, but it’s true. 3). The rise in elevation from the minimum point to the maximum (note: this unfortunatly won’t take into account cases in which you go up-and-down-and-up-and-down-and-up-again, but you’ll get an idea) and 4). A highly subjective rating as to the overall difficulty. This rating is based on a (somewhat riotous) public meeting of born and bred Valbona Malesori, who tended to class trails as either “Fine for Horses” – this means there’s no serious rock-hopping, and the trail is always at least 30 cm wide – but bear in mind that may be 30 cm with a rock wall on one side and a cliff drop on the other; “Veshtire” (Hard); or Shume i Veshtire (Very Hard) – which probably means that bits of it are overgrown, or hard to find, or you have to cross several avalanches or possibly climb up rocks, the falling off of which will almost certainly kill you, or any or all of the above. Basically, it’s something they’d sigh before setting off to do. Hm. We’re going to translate this into Easy, Hard and Very Hard. Bear in mind that this doesn’t relate to how tired you can expect to be (14 hours of an Easy trail should still make you pause and ponder if you’re up to it), nor does it mean that even the Easy trails won’t have parts that make you remind yourself not to look down. In fact, now that I think about it, even some of the trails that we’ve labelled “easy” include bits which you’d die if you fell down (thus deviating from the usual grievous-bodily-harm method). I suppose the label most serves to judge your skills against, which of course you won’t know until you’ve tried one or two, and seen how your idea of “Easy” measures up to ours, but there it is. We tried.

With that said, we’ve decided to give you as much information as we can, and rely on your good sense to decide what you’re capable of, or at any rate what you want to try. Thus descriptions of trails will tell you: 1). The total kms from the start to the end (sorry for pointing out the obvious, but this means you have to double this if you plan on returning the way you came). 2). How long we think it will take the average walker, one-way. A note here: We recommend that you use caution – or at any rate extreme skepticism – when asking local people to estimate walking time, as the fact is that your average Malesori 10 year-old can probably walk three times as fast as you – sorry, but it’s true. 3). The rise in elevation from the minimum point to the maximum (note: this unfortunatly won’t take into account cases in which you go up-and-down-and-up-and-down-and-up-again, but you’ll get an idea) and 4). A highly subjective rating as to the overall difficulty. This rating is based on a (somewhat riotous) public meeting of born and bred Valbona Malesori, who tended to class trails as either “Fine for Horses” – this means there’s no serious rock-hopping, and the trail is always at least 30 cm wide – but bear in mind that may be 30 cm with a rock wall on one side and a cliff drop on the other; “Veshtire” (Hard); or Shume i Veshtire (Very Hard) – which probably means that bits of it are overgrown, or hard to find, or you have to cross several avalanches or possibly climb up rocks, the falling off of which will almost certainly kill you, or any or all of the above. Basically, it’s something they’d sigh before setting off to do. Hm. We’re going to translate this into Easy, Hard and Very Hard. Bear in mind that this doesn’t relate to how tired you can expect to be (14 hours of an Easy trail should still make you pause and ponder if you’re up to it), nor does it mean that even the Easy trails won’t have parts that make you remind yourself not to look down. In fact, now that I think about it, even some of the trails that we’ve labelled “easy” include bits which you’d die if you fell down (thus deviating from the usual grievous-bodily-harm method). I suppose the label most serves to judge your skills against, which of course you won’t know until you’ve tried one or two, and seen how your idea of “Easy” measures up to ours, but there it is. We tried.

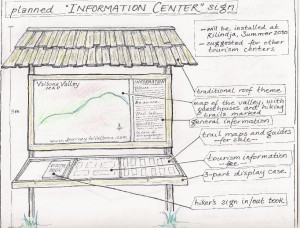

This information will be made available on this website (obviously); at the two Hiking Information Installations we’re building and putting at Rilindja (the east end of the valley) and at Fusha e Gjes (the west end of the valley); at each Hiking Trail Head Sign (due for installation in early summer 2011, as part of the UNDP’s KRTEP project); and on the individual Trail Maps which we’re working on developing (presumably also by summer 2011). I would like to point out here that all of our work has been funded by an extremely generous (absolutely in spirit, if modest in cash – I don’t want to imply that we’re swimming in moola) grant from the UNDP’s Kukes Region Cross-Border Cooperation Project.

This information will be made available on this website (obviously); at the two Hiking Information Installations we’re building and putting at Rilindja (the east end of the valley) and at Fusha e Gjes (the west end of the valley); at each Hiking Trail Head Sign (due for installation in early summer 2011, as part of the UNDP’s KRTEP project); and on the individual Trail Maps which we’re working on developing (presumably also by summer 2011). I would like to point out here that all of our work has been funded by an extremely generous (absolutely in spirit, if modest in cash – I don’t want to imply that we’re swimming in moola) grant from the UNDP’s Kukes Region Cross-Border Cooperation Project.

Now: How does all of this relate to the actual markings on the trails? Answer: It doesn’t! Yippee! The trail markings we used are adapted from the French Grande Randonnee system. Thus a single yellow “fleche” which I think translates as “mark” (10 cm par 2 cm, exactement!) indicates a Footpath (Rruga e Kemsore in Shqip). On the Malesori difficulty rating system, most of these don’t even merit consideration: it’s simply a pleasant way of getting from one place to another. We’ve used the Footpath markings for these pleasant walks and rambles around the valley bottom (which we’ll designate as “Very Easy,” or for very short (1 km or less) side trips from a main trail. These side trips may be more challenging than the walks around the valley bottom, but by the time you’ve gotten up to wherever they start from, they shouldn’t be harder than whatever you’re already committed to doing. Two marks, yellow above red (5 mm apart, bien sure!) are the most common, and indicate a local trail of some length, meaning that although it is of some length and difficulty, no matter how long or difficult it is, you start from Valbona, and at the end of it, you’re still in Valbona (although not necessarily where you started). A white mark over a red mark is used for trails which will take you out of Valbona, most notably to Theth, where all the trails are marked red and white (though not with the elegant precision of our marks! Tant Pis!).

Now: How does all of this relate to the actual markings on the trails? Answer: It doesn’t! Yippee! The trail markings we used are adapted from the French Grande Randonnee system. Thus a single yellow “fleche” which I think translates as “mark” (10 cm par 2 cm, exactement!) indicates a Footpath (Rruga e Kemsore in Shqip). On the Malesori difficulty rating system, most of these don’t even merit consideration: it’s simply a pleasant way of getting from one place to another. We’ve used the Footpath markings for these pleasant walks and rambles around the valley bottom (which we’ll designate as “Very Easy,” or for very short (1 km or less) side trips from a main trail. These side trips may be more challenging than the walks around the valley bottom, but by the time you’ve gotten up to wherever they start from, they shouldn’t be harder than whatever you’re already committed to doing. Two marks, yellow above red (5 mm apart, bien sure!) are the most common, and indicate a local trail of some length, meaning that although it is of some length and difficulty, no matter how long or difficult it is, you start from Valbona, and at the end of it, you’re still in Valbona (although not necessarily where you started). A white mark over a red mark is used for trails which will take you out of Valbona, most notably to Theth, where all the trails are marked red and white (though not with the elegant precision of our marks! Tant Pis!).

FAQ:

Is the water safe to drink? Yes, absolutely, and it’s delicious. Here in Albania it’s bottled and sold as “Valbona Water” which is our answer to Perrier. Personally, we tend to avoid drinking from rivers directly downstream from homesteads, but most of the “wild” water comes from glacial melt via limestone springs which act as natural filters. We’ve marked the particular springs used by local people when they’re in the bjeshket, although you should be aware that in the long dry days of August and early September, these may dry up, and some water should always be carried with you.

Are there Dangerous Animals? Yes, of course! “Lions and Tigers and Bears!” Well, No, actually, Wolves, and Pigs and Bears. In fact, these mountains boast the largest population of wolves in Europe, an estimated 400 (Ferdinand Bego, Tirana University). There are also numerous wild Boar (which are simply enormous, and make a ton of noise, by the way) and enough bears that you might quite possibly see one, especially if you’re anywhere near fruit trees. (This last statement is not as random as it sounds: There are abandoned orchards, left from the collectivization of communist times, in the Bjeshket, and . . . . the bears just love them). The boar are only dangerous if cornered (but then, very). Likewise the bears, while sometimes carnivorous, would probably prefer to stay out of your way. The wolves are a bit of a different question. Local wisdom is that in summer you really don’t have to worry about them. They move up to the tops of the mountains, following the game and flocks (but of course, that’s where you’re thinking of going), and in general they’d really rather eat almost anything else, than you. In winter, this is a different matter, and there are 40 days in January and February, called “Arbein” when no Malesori would think of leaving the house for any distance, alone, without a gun. They’re wolves. They’re intelligent and dangerous.  Three years ago they killed and ate three people in Hass, and before that, a bunch of people by the Kosovo border. At least, that’s what people tell me. Starting in late autumn, there are wolf tracks everywhere, and they’re sighted by someone at least once a week. Last winter, they killed and ate our dog, as they’ve eventually killed and eaten every dog we’ve ever had. A bunch of them visit our trash dump every night. I tell you all this so that you can make your own choices. Personally, I wander around everywhere, and haven’t been eaten yet (or seen a bear). I have seen signs of bears, like large rocks flipped in the forest (they look for bugs), as well as hairs left on “Bear Scratching Trees” – I’ve seen torn moss, and bear poop. I’ve been very close to wild boar who went crashing and galumphing through the underbrush around me, making a noise like a herd of Jabberwocky. I’ve stood more times than I can remember, scanning the horizon for whatever goat just dislodged a load of rocks, and sent them crashing down towards me, but only once have I heard near me the warning breathy whistle of a male goat who spotted me before I saw him. And I have seen wolves, who stood and looked at me with the most dignified and restrained curiosity, before turning to move off slowly. These are wild mountains, more wild than anywhere in Europe. Of course, this is the experience of only two years of wandering around here, and you may not see any of this, but then again, you might quite possibly, certainly more possibly than anywhere else. If you like this sort of thing, you’re in. If not, you might not want to go walking too far.

Three years ago they killed and ate three people in Hass, and before that, a bunch of people by the Kosovo border. At least, that’s what people tell me. Starting in late autumn, there are wolf tracks everywhere, and they’re sighted by someone at least once a week. Last winter, they killed and ate our dog, as they’ve eventually killed and eaten every dog we’ve ever had. A bunch of them visit our trash dump every night. I tell you all this so that you can make your own choices. Personally, I wander around everywhere, and haven’t been eaten yet (or seen a bear). I have seen signs of bears, like large rocks flipped in the forest (they look for bugs), as well as hairs left on “Bear Scratching Trees” – I’ve seen torn moss, and bear poop. I’ve been very close to wild boar who went crashing and galumphing through the underbrush around me, making a noise like a herd of Jabberwocky. I’ve stood more times than I can remember, scanning the horizon for whatever goat just dislodged a load of rocks, and sent them crashing down towards me, but only once have I heard near me the warning breathy whistle of a male goat who spotted me before I saw him. And I have seen wolves, who stood and looked at me with the most dignified and restrained curiosity, before turning to move off slowly. These are wild mountains, more wild than anywhere in Europe. Of course, this is the experience of only two years of wandering around here, and you may not see any of this, but then again, you might quite possibly, certainly more possibly than anywhere else. If you like this sort of thing, you’re in. If not, you might not want to go walking too far.

What happens if I get lost? There’s good news and bad news. The bad news is that there is very little official infrastructure here, and although the whole area is National Park, it does not currently have any of the services or resources that would often be considered normal elsewhere: so, no rangers, no vehicles and no dedicated communications system. There’s no one who offically has to look after you. The good news is that you are in the Malesi, where people have survived the difficult environment for centuries by helping each other and where there’s still an honor code about looking after visitors, so as long as someone knows around-about where you are, if you’re not back by dark, someone will (probably) come looking for you. They will incidentally also be able to skip over things that may have taken you hours and made you ask yourself why you ever wanted to do this. Should they spend their night out searching for you, however, they may quite reasonably be a bit pissed off (not that they’d ever show you), so we urge you to both let someone (presumably your host) know your plans – where you’re going and when you plan to be back – and to stick to your plan. A few serious suggestions here: One: Find out what time it gets dark. Dark is seriously dark here. Seriously. Two: Carry a flashlight. A good one, and maybe extra batteries. I’m the sort to pooh-pooh these kind of precautions, but if you’re caught out after dark (which, if you’re planning on spending any amount of time here at all, you almost certainly will be) you will definitely need it. With a flashlight, you can still find your way around. Without one, there’s really no choice but to sit still and wait for the sun to rise. I speak here from (what could easily have been bitter) experience. Three: As of 2010 there is cell phone reception everywhere in Valbona from (but only from) Eagle Mobile, although it can get a bit spotty at the western extreme of the valley. We plan on purchasing and making available to our guests (for a fee, to be sure, or at least a deposit) some extra phones, so you can take one with you. This will make all our lives simpler, but even if you’re not staying with us, I suggest you talk to your host and see if there’s a phone you can borrow. And of course, take someone’s number with you. That’s all I can think of for now.

What Happens if there’s a Medical Emergency? Same good and bad news, although the bad news is heavier. There is no doctor in Valbona, although there is a sort of registered nurse, but I’ve never heard of anyone going to him. If you’re seriously hurt, it means people coming up to carry you down, and then the hour drive to Bajram Curri where there is a hospital although, between you and me, Alfred says the doctors almost all drink like fish, so you have to visit them first thing in the morning, if at all. Anything serious is usually taken by people here to Tirana. In other words: Do NOT play around. If you have any doubt about your ability or safety, turn around and come back down the way you came. If even that seems perilous, use the cell phone you borrowed (see above) and call us. We’ll come get you. Avoid injury at all cost. Please.

List of Trail Names

Just out of interest, if you happen to be reading this in winter 2010-11, here’s a sneak peak of the list of the trails that are being worked on right now (well, as of last summer and whenever the weather lets us get out . . . . ). Sorry it looks so awful – no time to figure out how to make a table right now . . . .

Emertimi i Shtegut

Trail Names & Data

(max rise) (one way)

| Name | From – To | Time | Difficulty | Elev. | Dist. |

| 01 Kunji i Armve | (Klysyre – Cerem) | 14 ore | Easy | ||

| 02 Rruga e Ceremit | (Mas Kollata – Cerem) | 3 ore | Hard | ||

| 03 Lugi i Perslopit | (Cerem – Valbone) | 8 ore | Hard | ||

| 04 Maja e Kollata | (Lugi i Kollates – Pika Kollata) | 5 ore | Very Hard | ||

| 05 Quku i Valbones Rruga Kemsore | (Mas Kollata – Valbona) | 3 ore | Very Easy | 350 m | 8 km |

| 06 Gruka e Motines | (Gruka e Motines – Curraj e Eperm) | 14 ore | Hard | ||

| 07 | (Rrogam – Curraj i Eperm) | 14 ore | Very Hard | ||

| 08 Bjezhz | (Thepi i Begit – Valbone) | 6 ore | Very Hard | ||

| 09 | (Grunas – Kroi i Gjokolit) | 4 ore | Easy | ||

| 10 Rrogam & Qafa e Valbones | (Valbone – Thethi) | 5 ore | Very Hard | ||

| 11 | (Valbone – Rrogam) | 4 ore | Very Easy | ||

| 12 Maja e Rosit | (Valbone – Rosi) | 7 ore | Hard | ||

| 13 Liqeni Jezerces | (Pyramida 18 – Thethi) | 10 ore | Hard | ||

| 14 | (Rrethi i Bardh –Buni i Brahimit) | 4 ore | Easy | ||

| 15 Rruga e Puntorve | (Quku i Valbones –Lugi i Silkit) | 5 ore | Hard (easy?) | 1000 m | 6 km |

| 16 Quku i Llabudave | (Mas Kollata – Lugi i Silkit) | 3 ore | Hard | 1000 m | 3 km |

| 17 Shpella e Dragobise | (Mas Kollata –Kron i Tel i Zhon) | 3 ore | Easy | 420 m | 5 km |

| 18 Prroni i Picimalit | (Mas Kollata – Kron i . . .) | 3 ore | Easy | 320 m | 3 km |

| 19 Zhari i Bjezhz | (Kron – Lugi i Silkit) | 7 ore | Hard | 1200 m | 8 km |

| 20 Burimi i Picimalit | (? – Burimi i Picimalit) | 1 ore | Easy | 150 m | 700 m |

Trail Descriptions

Obviously, these will be a lot more complete (or even existent) once we’re done, but here’s what we had up before . . . .

05. Footpath to Liqeni i Xhemes (“Xhemes’ Lake”)

05. Footpath to Liqeni i Xhemes (“Xhemes’ Lake”)

Costs: Nothing!

Time: Half an Hour

Elevation Rise: None

Difficulty: Easy

Details:

This is a really nice little walk, just 220 meters from the Bajrum Curri road, and also connects with the footpath that runs through the beech woods from Rilindja to Quku i Valbones.

The lake is small, but truly beautiful nestled in the beech woods with its still, spring-fed reflecting water and Snake Mountain rising in the background. Albanians travel to visit it and it’s a perfect little walk for the night you arrive, to get to know the area and start exploring.

It’s also the prototype we developed this spring for trail marking throughout the valley to international standards, so you can make a point of admiring our footpath signs and trail markings!

12. Walk to Maja e Rosit (Rosi Mountain)

Costs: Guide € 50, Horse and Guide € 70

Time: One Day

Elevation Rise: 1250m

Difficulty: Moderate

Variations:

4 hours to border Montengro (easy) (3 hours back down)

+ 1 hour to the top of Rosi (view of lakes & Vuthaj in Montengro) (medium) (3.5 hours back down) or

+2 to the Lakes

Advice:

Bring food and water, as the spring along the way may be dry.

Details:

Departing from Quku i Valbones or Rilindja by 10am, you walk along the road from Bajrum Curri to Valbona. From the village you cross the river heading north and begin wending your way uphill through mountainous pastureland. The well defined path twists through rocks and boulders. Above this, you enter Beech Forest, passing stands of Thon bushes. After an hour walking, you arrive at the village of Kukaj (don’t get excited – “village” here means two or more houses. Kukaj has two.). Beyond Kukaj, you follow the gravel path of the new road which was blasted in the last year. It’s actually pretty. From here you climb to pine forest. The path grows steeper, and you emerge from the pines to climb mountain spines of alpine meadow. Forty minutes of hiking through open terrain bring you to the wide meadow where shepherds have built a small resevoir. If they’re around, they will welcome you into the small stone houses they use when resident with the sheep. From the meadow, you have clear views of Rosi, on the Montenegro border. Climbing to the top of Rosi takes one more hour. From Valbona to Rosi should take the better part of four hours. Returning by the same route downhill takes an additional two hours.

Slide show of the Walk to Rosi Mountain (Maja e Rosit):

![4076407449_cdd9127bc1_b[1] 4076407449_cdd9127bc1_b[1]](../../wp-content/uploads/2009/11/4076407449_cdd9127bc1_b1-225x300.jpg)

Useful info

Useful info